Basic income could solve global poverty and stop environmental destruction, study finds

By Alex Walls

Providing a basic income could boost global gross domestic product (GDP) by $US163 trillion while acting to curb environmental degradation, UBC research has found

An analysis of 186 countries found that providing basic income, or regular, set payments to all adults in the world, could boost global GDP by about 130 per cent. For every dollar invested, approximately US$4 to $7 of economic impacts could be generated, according to the study published today in Cell Reports Sustainability, which the researchers believe is the largest of its kind to date.

“Environmental damage and poverty both pose huge risks to society,” said senior author Dr. Rashid Sumaila, a professor in the UBC Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries (IOF) and the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. “By requiring that major polluters pay to clean up their own messes, or the ‘Polluter Pay Principle’, you have a creative approach to address both issues by de-incentivizing environmental pollution through taxation and the removal of existing environmentally harmful subsidies, and using those funds to support a basic income.”

Benefits versus costs

Providing a basic income to everyone in the world living below the poverty line could boost global GDP by $49 trillion or about 39 per cent of current GDP.

The researchers estimated the cost of offering a basic income to the entire global population to be about $41.6 trillion, or about 30 per cent of current GDP. When provided to just those living below the poverty line, the cost was $7.1 trillion.

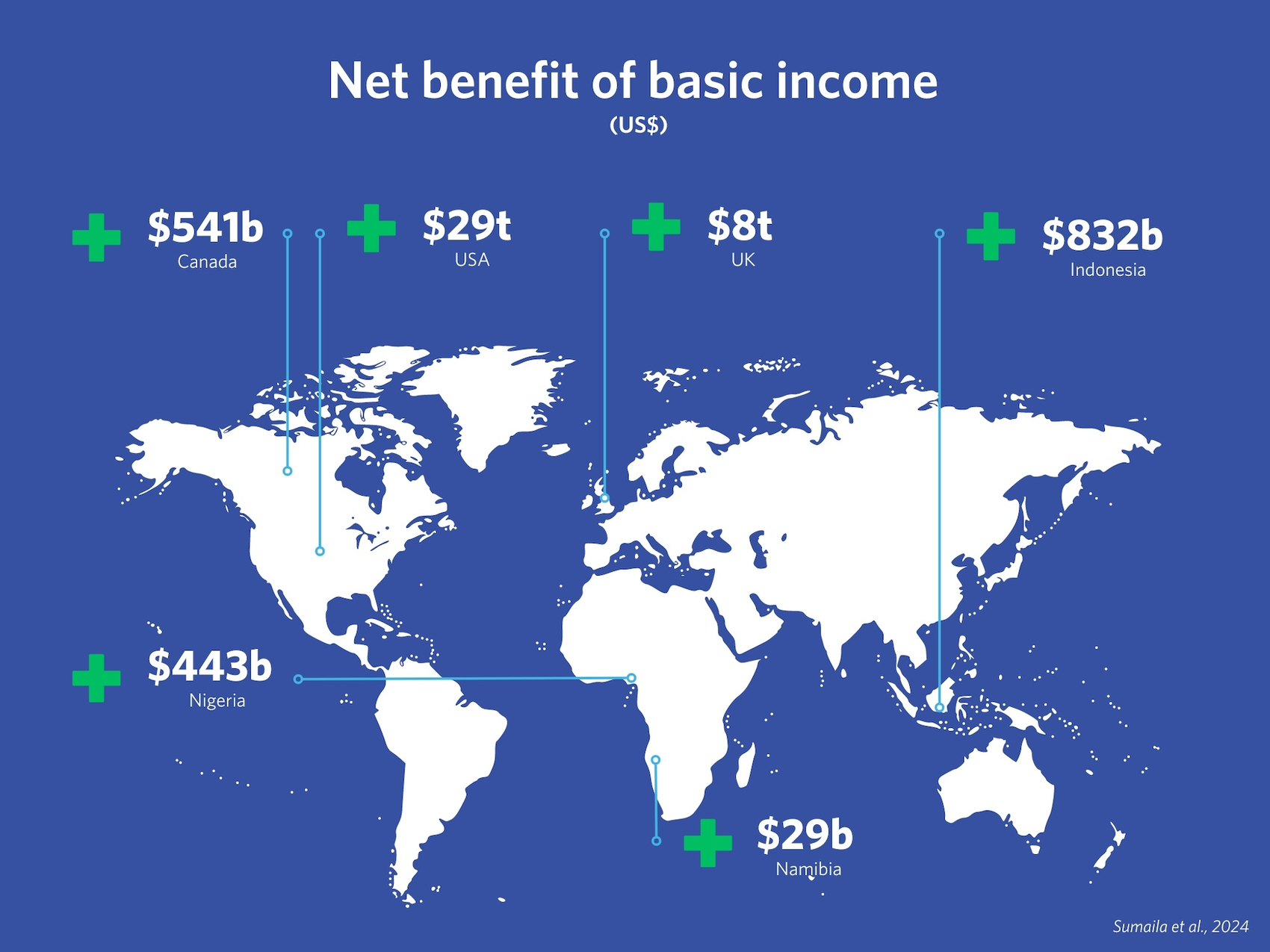

In Canada, the net benefit of providing a basic income to the country’s population would be $541 billion. “About 10 per cent of the Canadian population live below the poverty line. Thus, this is a global problem,” said Dr. Sumaila.

“Basic income could also potentially contribute in helping to counteract rising inequality in the face of shocks and extreme events,” said co-author Dr. Carl Folke, co-founder of the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Financing basic income while reducing environmental harm

The researchers noted that there are a number of ways to finance basic income that also reduce environmental degradation, but focussed specifically on carbon taxes given the global push to reduce emissions. While the research looks at a flat tax on carbon production, governments could design taxes to target major polluters and degraders of biodiversity including the oil and gas industry.

Implementing a flat tax of $50 to $100 per tonne of carbon emitted through fossil fuel use could raise about $2.3 trillion, enough to fully fund basic income for people living below the poverty line in Asia, Europe and North America combined.

Another source of financing could come from redirecting environmentally harmful fisheries subsidies, or government payments that incentivize overcapacity and lead to overfishing, said co-author Dr. Louise Teh, IOF research associate. “In a recent study, we showed that the amount spent on harmful fisheries subsidies in 11 out of the world’s 30 least developed coastal countries would be enough to lift their fishers out of extreme poverty.”

Barriers beyond financial cost

Challenges to implementing a basic income extend beyond the financial cost and include implementation difficulties and perceptions that it may weaken incentives to work and save. However, real-world examples of its efficacy exist, including in Alaska, where part-time work increased by 17 per cent when basic income was implemented, and in Indonesia, where implementation contributed to a decline in deforestation. Successful implementation depends on many factors, including financial considerations and political resolve. Governments must ensure they design effective programs, the researchers say.

While basic income might seem like an extraordinary measure, it could serve as a proactive economic strategy, providing a more universal social safety net while fortifying against future disasters, including pandemics such as COVID-19 and climate disasters. “In short, extraordinary times call for commensurate measures,” said Dr. Sumaila.

Alex Walls is a writer with UBC Media Relations. This article was republished from UBC Media Relations on July 22, 2024. Read the original article here. To republish this article, contact UBC Media Relations.