It’s time to accept, not resist, rising sea levels

By Carolyn Ali

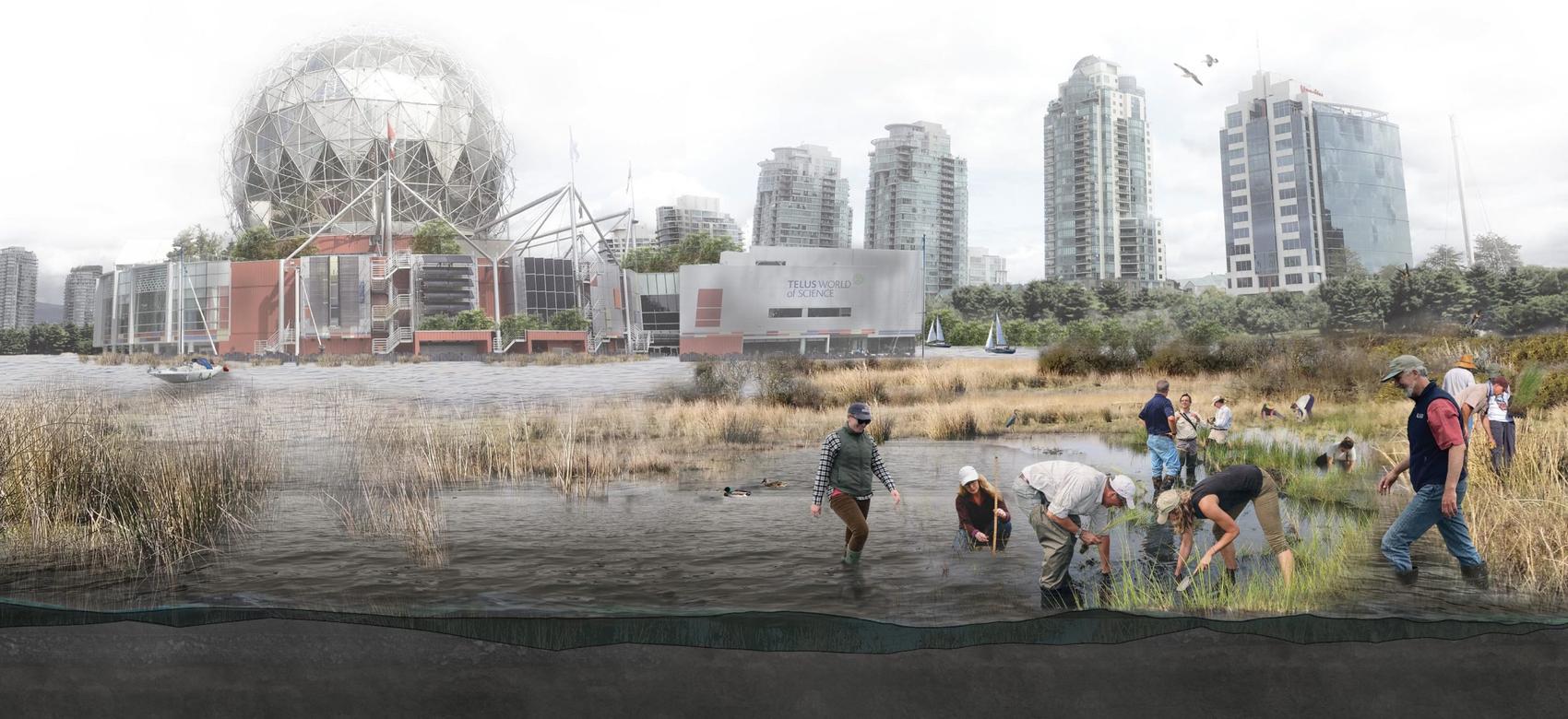

Coastal communities could adapt to climate change with proactive, nature-based solutions

Landscape architect Kees Lokman understands that people don’t want to visualize their homes and coastal communities underwater. Conversations around rising sea levels and flooding can be challenging as many people want a status-quo solution that aims to keep the shoreline in place where it is now.

“Traditionally, the way we’ve dealt with protecting our coast is through seawalls and dykes,” he explains. “For settler municipalities, our values have very much been tied up in protecting infrastructure and development.”

But as the director of UBC’s Coastal Adaptation Lab, Lokman says we need to discuss solutions that are based on a broader range of values. These include prioritizing ecosystems, habitat conservation, biodiversity and wildlife, as well as addressing inequities related to Indigenous sovereignty, food security and the livelihoods of people in coastal communities.

He says that in general, people don’t notice sea level rise and don’t think much about the consequences until a king tide affects their community or they see news reports of floods, storms and tsunamis. “One of the challenges around awareness is that change is very incremental,” says Lokman. “But that’s also one of the reasons why we can do something about it. We need to plan to adapt now.”

Living with water

In British Columbia, 80 percent of the population lives within five kilometres of the coast. Sea levels around BC are expected to rise 0.5 metres by 2050 and 1.2 metres by 2100, flooding coastal communities.

While we can still work to mitigate global warming, Lokman says, it’s too late to stop rising sea levels. “That’s why our project is called Living with Water,” he explains. “We can’t fight it anymore.”

“If we’re proactive, the disruptions to our lives will be much less than if we ignore the issue.”

Kees Lokman

Director of UBC’s Coastal Adaption Lab

The Living with Water project aims to develop an integrated regional response to sea level rise. As the principal investigator, Lokman is working with partners across BC’s southern coast including UBC and other leading universities, Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) and Səl̓ílwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nations, municipalities, legal experts and the BC government.

One of the project’s key drivers is to integrate community values and Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into coast flood risk assessment. It also aims to help communities share perspectives and understand and evaluate the merits and trade-offs of different approaches.

For example, instead of building more dykes and seawalls, we could protect shorelines from waves using nature-based methods grounded in Indigenous knowledge. We could use solutions like wetlands and salt marshes to act as natural buffers against flooding and to maintain wildlife habitat. We could transition farmland to grow crops that could survive seawater floods, rather than trying to hold back water with dykes.

Lokman urges people to be open-minded and visualize solutions. “Change will be disruptive. It won’t be ‘win-win’ for everyone. But not all change has to be bad,” he says. “If we’re proactive, the disruptions to our lives will be much less than if we ignore the issue.”

In any case, he says, trying to maintain the status quo won’t serve us. “If you live near the ocean, try to visualize the view if there’s a six-to-eight metre dyke built in front of your home. Or imagine what will happen when you are required to have flood insurance, or can no longer get flood insurance, or the government won’t bail you out. How will the experience of living in that place be different?”

He notes that the word “flood” carries a negative connotation, but it’s actually part of the natural cycles of rivers and oceans. “We shouldn’t be surprised if we occupy certain areas that water will come in,” he notes. “We can adapt by learning to accommodate it.”

Nature-based alternatives

Allowing water to flow inland can have benefits. Here are a few methods that Lokman says we could use to adapt to rising sea levels. “Many of these solutions can work together,” he says. “It’s not one and done.”

Living dykes

“A traditional dyke prevents coastal ecosystems from moving inward,” Lokman explains. “Building a dyke means sacrificing the marsh.” Birds, spawning areas for fish, entire food chains and livelihoods depend on these areas.

Traditional dykes have a high three-to-one gradient. With living dykes, the seaward side has a much lower gradient that allows plants to occupy the area as well as salt marshes and other coastal ecosystems when sea levels rise. These things help to reduce the force of waves.

Sediment diversion

This involves raising the marshes and wetlands so they can establish themselves over time with rising sea levels.

Clam gardens

Built at the low tide line, these rock walls act as a submerged breakwater. They create a habitat for clams and other species, provide food security and stabilize and extend beaches. “First Nations have been using this method for 12,000 or 13,000 years,” he says. “There’s a real interest by many First Nations to reclaim knowledge around this and reclaim some of these sites.”

Beach nourishment

In areas where beaches are being eroded by waves, this involves spraying fine-grain sediment on the beach to replenish the sand. “Wreck Beach in Vancouver is a nourished beach,” Lokman notes. “It helps to break the waves and protect the cliffs that are behind it.”

Moving to higher ground

Lokman says that we also need to be discussing “managed retreat”, or policies that can encourage, facilitate or mandate people to move to higher ground. “Rather than trying to protect certain areas, you allow the water in and allow the creation of valuable ecosystems that help to attenuate the waves,” he says.

These are difficult conversations to have, he says, as relocating communities is traumatic. Managed retreat also has different issues and implications for different communities. Indigenous peoples, for example, have lived in some areas for thousands of years, while settler communities may have a relatively new connection to certain areas.

“There are tremendous opportunities to think about decolonization alongside issues of coastal adaptation.”

Kees Lokman

Director of UBC’s Coastal Adaption Lab

“A lot of our municipalities are on unceded territories,” Lokman says. “There are tremendous opportunities to think about decolonization or integrating land-back principles alongside issues of coastal adaptation.”

Some of these solutions don’t necessarily involve relocating people right away; it could be over a 50-year time period. For example, instead of a family selling an old house in a flood plain and the new owners building a new one, the government could buy that house and rent it back or clear the land.

While sea levels may not force drastic change right away, Lokman says the time to have these discussions is now. “We all have a part to play in thinking about what a different future might look like and how we can participate in it.”

Carolyn Ali is a writer for UBC Brand and Marketing. This article was published on October 15, 2021. Story with files from Lou Corpuz-Bosshart, UBC Media Relations. Feel free to republish the text of this article, but please follow our guidelines for attribution and seek any necessary permissions before doing so. Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence.