Banning ‘Maus’ only exposes the significance of this searing graphic novel about the Holocaust

By Biz Nijdam

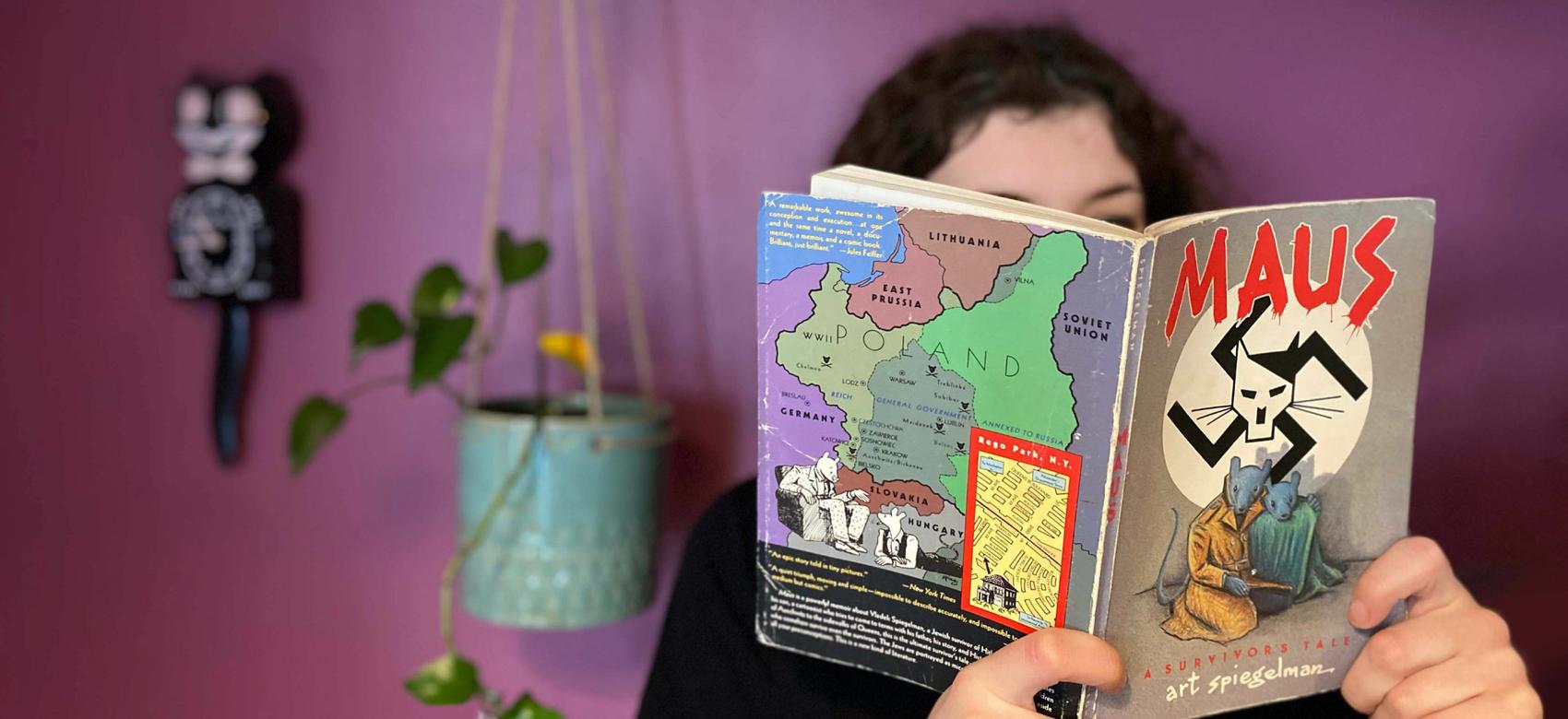

A school board in Tennessee voted unanimously in favour of removing the graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman from its Grade 8 language arts curriculum in January. Maus is based on interviews with Spiegelman’s father, Vladek Spiegelman, a Polish Jew and Auschwitz survivor, and won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for its searing and innovative visual and narrative exploration of the darkest period of German history.

The McMinn County’s Board of Education cited “rough, objectionable language” and the cartoon drawing of a nude woman as their primary objections.

However, with editions flying off the shelves and comic book stores giving away copies, the McMinn County school board has, in fact, improved Maus’s distribution, getting it into the hands of more readers.

Graphic novel and historical representation

Maus explores Spiegelman’s parents’ life in Poland and their internment at Auschwitz. Vladek Spiegelman’s experience of the Holocaust and its aftermath — including the 1968 suicide of Art Spiegleman’s mother, Vladek’s wife, Anja — is filtered through cartoonist’s narrative and visual account. He portrays the Holocaust as a conflict between cats, mice and pigs where Jews are drawn as mice, Germans as cats and Poles as pigs.

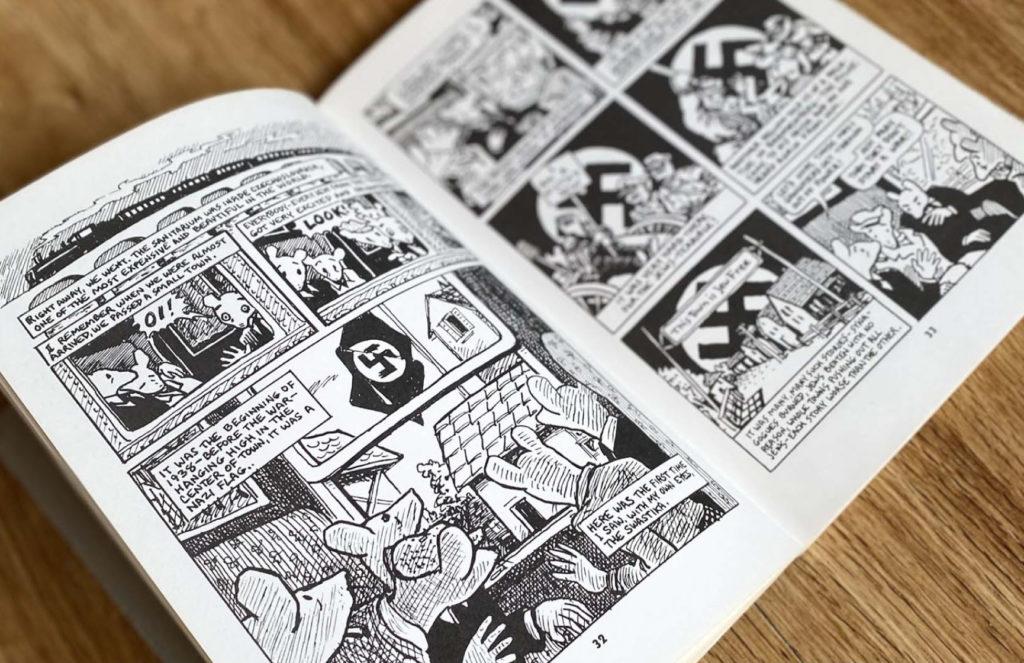

Spiegelman’s use of animals met some controversy including among some Polish readers, as well as some in the Jewish community who saw in mice the stereotype of Jews as pathetic and defenseless creatures. Yet Spiegelman noted that his anthropomorphized mice intentionally challenged Nazi propaganda that likened Jews to rats. For example, a teaching guide characterizes Spiegelman’s Jewish mice as “a barbed response to Hitler’s statement ‘The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human.’” His mice, Spiegelman wrote, “stand upright and affirm their humanity.”

Maus was first published in Françoise Mouly and Spiegelman’s comics anthology RAW from 1980 onward, before the first six chapters were published in 1986 as Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale and the latter five chapters were published in 1991 as Maus II: A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles.

The graphic novel’s 1992 Pulitzer Prize win (in the “Special Citations and Awards” category) drew academics’ attention to the comics medium for the first time.

Now heralded as one of the greatest graphic novels of all time, Maus successfully established comics as an important feature of contemporary culture and historical representation. It opened the floodgates to comics addressing serious subject matter and changed the medium’s relationship with history.

Ethics of representing the Holocaust

While some may be encountering Maus for the first time in their newsfeeds, comics fans, teachers and literary and cultural studies scholars have known the importance of Maus in teaching and learning for decades.

Maus made comic books visible and legitimate in ways that had been previously inconceivable. As my research has explored, Maus also redefined the medium’s potential through its engagement with what is known in Germany as Vergangenheitsbewältigung, overcoming the past or coming to terms with the history of Nazism. At the same time, Maus prompted important popular and scholarly debates on the ethics of representing the Holocaust.

For example, literature professor Marianne Hirsch examined the role of photography in Maus in a 1992 essay, providing the scholarly foundation for her subsequent work on transgenerational trauma.

German and comparative literature professor Andreas Huyssen examined the ethics and esthetics of remembering the Holocaust by looking at Maus’s narrative strategies. In particular, Huyssen turned to Maus as an important example of how to move debates on representing the Holocaust beyond a focus on the “proper” depiction of historical trauma. Instead, Huyssen analyzed Maus’s ability to shock and jar its reader “through ruptures in narrative.” As Huyssen notes:

“[T]he telling of this traumatic past … is interrupted time and again by banal everyday events in the New York present. This cross-cutting of past and present, by which the frame keeps intruding into the narrative … points in a variety of ways to how this past holds the present captive, independently of whether this knotting of past into present is being talked about or repressed.”

Huyssen found that Maus demonstrated the power of modernist Holocaust commemorations that steer clear of “official Holocaust memory” and its rituals while incorporating a critique of representation itself.

Similarly, historian Hayden White looked to Maus as a case study in his discussion on the relationship between history and narrative.

White questioned the belief that the uniqueness of Nazism and the Nazi “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” — the mass genocide of Jews — might set limits on its portrayal, insisting that there are no unacceptable modes of historical narrative. White argued that the destabilizing of the division between fact and fiction as seen in Maus is well-suited to representing what may otherwise seem “unrepresentable,” namely, the Holocaust as well as the experience of it.

Multi-layered process of ‘witnessing’

However, with the media attention that the recent ban of Maus is receiving, it’s likely that more readers than ever are going to come to regard Spiegelman’s graphic art as an essential text in Holocaust education.

Maus’s multi-generational memoir laid the groundwork for comics, and graphic memoir in particular, to become an essential form for remembering the Holocaust and communicating its legacy of transgenerational trauma. Even today, 30 years after Maus’s Pulitzer award, graphic novelists are turning to comics to explore these issues. For example, German-American illustrator Nora Krug’s 2018 Belonging offers new perspectives on German guilt through her graphic novel that is both memoir and scrapbook.

Recently, researchers are looking again to comic art to educate on the Holocaust and genocide more generally. Germanic and Slavic studies professor Charlotte Schallié from the University of Victoria is leading a SSHRC-funded project called Narrative Art and Visual Storytelling in Holocaust and Human Rights Education.

In an interview, Schallié said this focus was inspired by her son’s discovery of Maus as a reluctant reader at age 11. She explained how comics are foundational in Holocaust education and that Maus is an essential piece of graphic literature for both middle- and high-school curricula. According to Schallié, Spiegelman’s complex esthetic modes of representation complicate the genre of survivor testimony to draw attention to the multi-layered process of witnessing. “To ban Maus in the middle-school curriculum,” she said, “does a great disservice to students.”

Biz Nijdam is an assistant professor in German Studies and a lecturer in UBC’s Department of Central, Eastern, and Northern European Studies. This article was republished from The Conversation on February 16, 2022, under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.