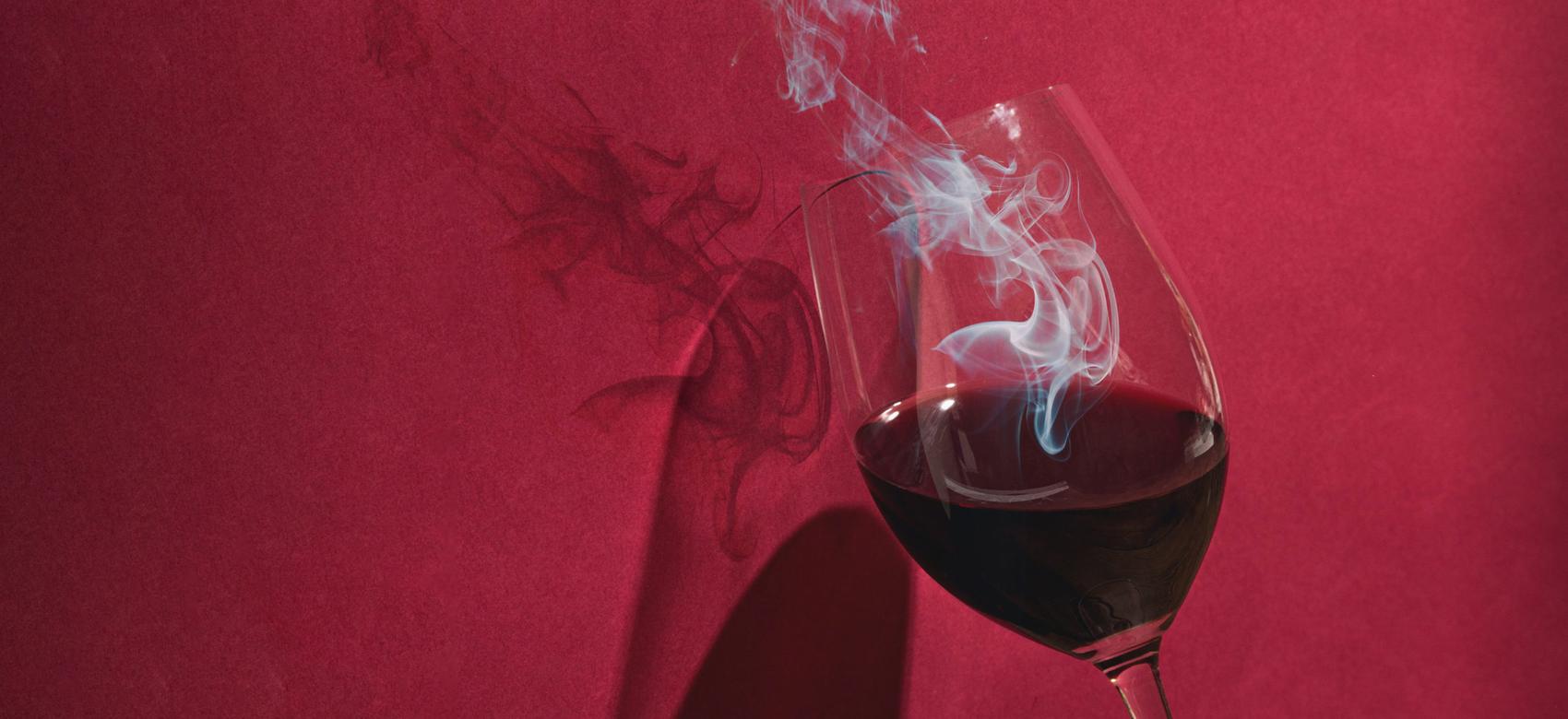

How wildfires are tainting grapes with smoke and threatening the wine industry

By Dr. Wesley Zandberg

Fires can destroy vines and other vineyard infrastructure, such as the vine posts or irrigation systems, but even distant fires pose a risk to wine grapes, due to a phenomenon known as smoke taint. Smoke taint refers to the undesirable ashy, smoky aroma of wines produced from grapes exposed to wildfire smoke while ripening.

British Columbia has already surpassed the 10-year average for number of forest fires and total hectares burned. Many of these fires are near the Okanagan Valley, an important Canadian wine-producing region.

As wildfires continue to edge closer to towns and agricultural areas, grape producers and wine makers in the Okanagan must once again deal with this increasingly frequent threat.

As an analytical chemist, I have been studying how wildfire smoke leaves a chemical signature in grapes, and researching ways in which we can prevent smoke taint from affecting wine produced in areas subject to these forest fires.

Smoke taint: A stealthy threat

Many may have noticed how the aroma of wood smoke, say from a camp fire, permeates clothing or hair, or how smoking a salmon imparts a delightful aroma to the meat. Smoke does not taint wines in the same way.

Wine grapes readily absorb the compounds responsible for smoky aromas, but once inside the grape, they are almost immediately transformed by enzymes into forms that cannot be perceived by smell or taste. The problem is, the yeasts used for wine fermentation are able to regenerate the original smoky aromas.

Smoke poses a massive threat to B.C.’s wine industry. Most tainted wines smell bad and are unsellable. What’s worse is that these horrid odours usually remain undetected until after wineries have invested money and effort to harvest and ferment tonnes of grapes that may smell perfectly fine.

The economic impact of smoke taint is hard to pin down exactly, but it may be severe. For example, the Australian wine industry has recorded losses of up to 300 million Australian dollars (the equivalent of C$276 million) due to bushfire smoke. In B.C., while some smoke-tainted wines may be sold as novelty items, the vast majority of it is simply undrinkable and must be thrown away.

The chemistry of smoke taint

The aroma of smoke is due in large part to a class of compounds known as volatile phenols. Volatile phenols readily evaporate at reasonably low temperatures, meaning they can be easily smelled. Some volatile phenols are so pungent, they can be detected by smell at concentrations in the low part-per-billion range, which is roughly equivalent to mixing a teaspoon into an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

When volatile phenols enter either ripening grapes or their leaves, they are almost immediately detoxified through a process is generally known as glycosylation, where volatile phenols are chemically linked to simple carbohydrate molecules like glucose.

The volatile phenolic-glycosides produced in this process are not volatile, and lack an aroma. Some evidence shows that they are metabolized by bacteria in people’s mouths, contributing to the perception of smoke taint up the back of the throat or mouth that steadily begins to intensify after a second or third sip of wine.

But the really big problem occurs when the yeast used to ferment the grapes break down the volatile phenolic-glycosides. This regenerates smoky aromas in grapes that smelled perfectly fine. Interestingly, grapevine smoke exposure does not always lead to a tainted wine. Sometimes desirable levels of volatile phenols are leached into wines aged in oak barrels. My colleagues and I have used sensitive analytical instruments to unravel these chemical mysteries.

Can smoke taint be detected before grapes are harvested?

Since 2015, students in my laboratory at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus, in Kelowna, have been spearheading Canadian research on smoke taint.

Prior to this, the bulk of the research on smoke taint had been performed by Australian researchers. While Australia, like B.C., faces frequent wildfires, we reasoned that the differences in fuel sources, which would influence the types of specific volatile phenols present in smoke, and grape growing conditions would mean that chemical evidence of smoke taint in wine grapes would be unique for each region.

We devised a method to carefully simulate the effects a forest fire on B.C. vineyards, using ponderosa pine needles, bark and local soil organic matter as our fuel source.

We reasoned that by boiling grape juice in hydrochloric acid and chemically mimicking the yeast-induced transformations of volatile phenolic-glycosides that occur during wine-making, we would be able to rapidly predict the concentration levels of volatile phenols after fermentation.

Our research showed that smoke-derived volatile phenols enter grapes and are transformed into non-volatile forms in under one hour. We know that these smoke-derived volatile phenols are actually transformed by grapes since they are detectable only after fermentation or boiling in acid. But, interestingly, they are not detectable solely as glycosides.

Identifying how grapes chemically trap volatile phenols will help winemakers devise methods to remove them from grape juice or wine. This identification is also important because yeasts are able to release the free, smelly volatile phenols from these still unidentified forms.

An ounce of prevention

While efforts to identify how grapes chemically alter volatile phenols are ongoing, we have begun to use our tools and methods to focus on preventing smoke taint directly in the vineyard.

A preliminary screening of three approved agricultural sprays revealed one product, intended for use on cherries, significantly reduced concentrations of volatile phenols in smoke-exposed grapes at harvest. But, after a follow-up study at three Okanagan vineyards failed to replicate these effects, our search continues.

We have discovered, however, that red table grapes, available year-round in Canadian grocery stores, mimic the transformations of volatile phenols observed in on-the-vine wine grapes. This discovery means that we will be able to perform initial screens of dozens of variables and products in the lab, unconstrained by the Canadian grape-growing season.

In the meantime, Okanagan vineyards and wineries have to carefully evaluate their crops, monitoring for volatile phenols, sugar-coated or otherwise.![]()

Dr. Wesley Zandberg is an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. To republish the article, please visit the original article and follow their guidelines.